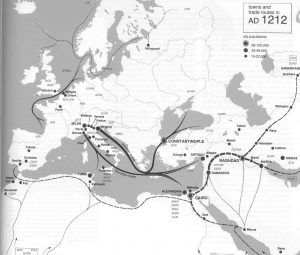

The Crusades did not mark the beginning of trade between Muslim and Christian lands in Europe. Italian merchants traded across the Mediterranean with Constantinople, Syria and Egypt, and Spanish Muslims and Christians traded actively and produced fine goods for sale. Sicily, under Muslim rule and then under Norman rule, was a source of contact and production of goods. Among the most precious articles of trade were metal wares, silk textiles, and glass, as well as some food stuffs, dyes and perfumes.

The contribution of the Crusades was that trade increased as Europeans traveled and became more familiar with exotic goods. Increased contact and trade was part of the reason for the rise of towns and cities in western Europe, starting in Italy.

Trade and travel meant people saw, heard, tasted and touched new things, and influences in the arts and lifestyles moved with them, bringing new styles of building, decoration, clothing, cooking and music—for those wealthy enough to afford the new things. In the following sections, read about some objects of fine living that entered Europe in part as an outcome of the exchanges during the Crusades.

Map source: http://academic.udayton.edu/williamschuerman/Trade_Routes.jpg

Spanish Muslim Traveler Ibn Jubayr Speaks about Armies and Caravans in the 12th Century

From Muhammad ibn Ahmad Ibn Jubayr, (Roland Broadhurst, translator), Travels of Ibn Jubayr: Being the Chronicles of a Medieval Spanish Moor Concerning His Journey to the Egypt of Saladin, the Holy Cities of Arabia, Baghdad the City of the Caliphs, the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem, and the Norman Kingdom of Sicily (London: Cape, 1952), pp. 300–301.

Introduction

Ibn Jubayr (b. 1145) was a resident of al-Andalus, or Muslim Spain, during the 12th century. His journey was the result of an unfortunate incident at the court of his ruler. It seems that the ruler forced the pious scholar Ibn Jubayr to taste an alcoholic beverage in jest. Ibn Jubayr was so disturbed that it caused the ruler to regret his actions. To make up for the outrage, he is said to have given Ibn Jubayr a quantity of gold. To atone for his sin of weakness, Ibn Jubayr vowed to use the money for a Hajj, or pilgrimage journey to Makkah. He did so, and made a tour of several other places around the Mediterranean. Historically, his travel account is especially interesting since he traveled during the Crusades, at the time of Salah al-Din (Saladin). He was an excellent observer of his time.

From Ibn Jubayr’s Travels in Egypt, Palestine, and Syria:

One of the astonishing things that is talked of is that though the fires of discord burn between the two parties, Muslim and Christian, two armies of them may meet and dispose themselves in battle array, and yet Muslim and Christian travelers will come and go between them without interference. In this connection we saw at this time, that is the month of Jumada al-Ula [in the Islamic calendar], the departure of Saladin with all the Muslims troops to lay siege to the fortress of Kerak, one of the greatest of the Christian strongholds lying astride the Hejaz road [the pilgrimage route to Makkah] and hindering the overland passage of the Muslims. Between it and Jerusalem lies a day’s journey or a little more. It occupies the choicest part of the land of Palestine, and has a very wide dominion with continuous settlements, it being said that the number of villages reaches four hundred. This Sultan invested it, and put it to sore straits, and long the siege lasted, but still the caravans passed successively from Egypt to Damascus, going through the lands of the Franks without impediment from them. In the same way the Muslims continuously journeyed from Damascus to Acre (through Frankish territory), and likewise not one of the Christian merchants was stopped or hindered (in Muslim territories).

The Christians impose a tax on the Muslims in their land which gives them full security; and likewise the Christian merchants pay a tax upon their goods in Muslim lands. Agreement exists between them, and there is equal treatment in all cases. The soldiers engage themselves in their war, while the people are at peace and the world goes to him who conquers. (Ibn Jubayr, born 1145) (CITATION: pages 300–301)

Metalwork

Ayyubid Canteen with Christian and Islamic Motifs

On the shoulder of the canteen are bands with an inscription in Arabic, with a blessing wishing the owner glory, security, prosperity and good fortune, as well as victory and enduring power, “everlasting favor and perfect honor.” The middle band is an animated inscription formed by a procession of real and fantastic creatures, human horsemen and camels whose bodies make up the strokes of the Arabic letters. This extremely intricate inscription reads: “Eternal glory and perfect prosperity, increasing good luck, the chief, the commander, the most illustrious, the honest, the sublime, the pious, the leader, the soldier, the warrior of the frontiers.” (Atil, p. 124) The lowest band is a series of 30 roundels with a hawk attacking a bird, and seated figures of musicians and figures drinking, and bowls of fruit. The bottom of the canteen has twenty-five standing figures divided by pillars. They represent saints in robes with books, censers and others show soldiers with weapons. One set may show Mary and the Angel Gabriel. The central ring on the bottom shows a scene of knights in a tournament. Even the neck of the canteen has intricate inlaid inscriptions and designs.

The patron who commissioned this remarkable piece from a Syrian or Iraqi artisan was a Christian familiar with knightly endeavors—perhaps a Crusader. The canteen is one of the most spectacular examples of this kind of Islamic metalwork.

Image credit: CANTEEN, Ayyubid period, mid-13th century, Mosul School, http://www.asia.si.edu/collections/edan/object.php?q=fsg_F1941.10.

Brass, silver inlay, DIMENSION(S) H x W (overall): 45.2 x 36.7 cm (17 13/16 x 14 7/16 in), Syria or Northern Iraq, Purchase — Charles Lang Freer Endowment, Freer Gallery of Art, ACCESSION NUMBER F1941.10

Source for text: Esin Atil, W. T. Chase, Paul Jett, Islamic Metalwork in the Freer Gallery of Art (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Freer Gallery of Art, 1985), pp. 125–33 (canteen); pp. 137–43 (Basin).

Ayyubid Basin with Christian and Islamic Motifs

On the outside of the large basin (50 cm/20 inches in diameter) are scenes from Jesus’ life: the Annunciation, the Virgin and Child enthroned, the miracle of raising Lazarus from the dead, Christ’s entry into Jerusalem, and a scene that might represent Christ’s Last Supper with his disciples. Other designs on the outside of the basin show a polo game and a procession of realistic and imaginary animals. Between them are seated musicians in round medallions. Inside the basin, a row of thirty-nine standing figures separated by pillars and arches represent saints or other important persons. The inscription around the inside rim celebrates the ruler Najm al-Din Ayyub as “Our master, the illustrious, the learned, the efficient, the defender, the warrior, the supported, the conqueror, the victor, lord of Islam and the Muslims…may his victory be glorious.” Whether commissioned by a Muslim or Christian patron for the Sultan, the combination implies religious tolerance in thirteenth-century Ayyubid Syria. Najm al-Din lost his life in Egypt in 1249 while fighting against the Crusade of St. Louis.

Image Credit : Basin, Ayyubid period, Reign of Sultan Najmal-Din Ayyub, 1247–1249, http://www.asia.si.edu/collections/edan/object.php?q=fsg_F1955.10

Brass, inlaid with silver, DIMENSION(S) H x W x D: 22.5 x 50 x 50 cm (8 7/8 x 19 11/16 x 19 11/16 in), Syria, Probably Damascus, Freer Gallery of Art, ACCESSION NUMBER F1955.10 Purchase — Charles Lang Freer Endowment

Source for text: Esin Atil, W. T. Chase, Paul Jett, Islamic Metalwork in the Freer Gallery of Art (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Freer Gallery of Art, 1985), pp. 125–33 (canteen); pp. 137–43 (Basin).

Silk Textiles

The secrets of silk cultivation and weaving complex patterns called brocades belonged first to China. Silk weaving spread along the Silk Roads to Byzantine and Sassanian Persian royal workshops before the rise of Islam, and was adopted by the Muslim Abbasid caliphs, who established their own caliphal workshops. Such royal fabrics were possessed only by the most elite of rulers and courtiers. Their designs reflected symbols of the ruler in the shape of mythic animals, and Muslim caliphs often wove Arabic inscriptions of blessings and of their names. They were given as gifts of robes of honor to show royal favor. It was the ultimate in “power dressing” to be able to wear such a garment.

The technology of silk cultivation, dyeing, and complicated brocade looms spread across the Mediterranean with Islam, carried to Egypt and across North Africa, Spain, and Sicily. Brocade workshops expanded beyond the courtly production and began to produce fine textiles for export. Medieval churches and nobles imported brocades from Spain, Sicily, and Fatimid Egypt for wall hangings, church decoration and vestments (priestly garments worn while celebrating mass). When Sicily fell to the Normans, they inherited silk production centers. As other centers in Italy began to produce silk brocades, they copied the techniques and patterns so well that it is difficult to tell their origin, but imports also continued from the East.

We know what uses these brocades served from paintings made after the thirteenth century in Italy, and later in Spain. Giotto’s Lives of St. Francis in the basilica at Assisi were the earliest Italian paintings showing imported Islamic silk brocades. The image here shows Saint Francis Appears to Pope Gregory IX in a Dream, painted between 1296 and 1305, in the Basilica of St. Francis at Assisi, Italy. A wall hanging behind the pope has intricate geometric designs in bright silk, and a band that imitates Arabic script, which in the original would have had a blessing or other repeated phrase for the owner. Another hanging is a canopy over the bed, and these rich cloths cover the bed and a bench in front of it. The fabrics are probably Spanish imports. In Syria and Egypt, animal patterns were common, which were often copied in early Italian brocade workshops. Even sacred paintings of the Madonna and Child showed the Virgin Mary clothed in fabrics with Islamic designs and Arabic script.

This illustrates that the beauty and luxury of the fabrics was more important than any religious references. These fabrics are also an important sign of trade across the Mediterranean, which only increased as more products from the East became known in Europe.

Image credit: Giotto di Bondone (d. 1337), Dream of Pope Gregory IX, from the fresco series of the Legend of St. Francis in the Upper Church, Basilica of San Francesco, Assisi; Date: before 1337, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Saint_Francis_cycle_in_the_Upper_Church_of_San_Francesco_at_Assisi.

Source for text: Rosemond Mack, From Bazaar to Piazza: Islamic Trade and Italian Art, 1300–1600 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002), pp. 27–22; Alavi and Douglass, Emergence of Renaissance: Cultural Interactions between Europeans and Muslims (Fountain Valley, CA: Council on Islamic Education, 1999), pp. 263–74.

Madonna and Child

This painting of the Madonna and Child shows the Virgin Mary against a gold background with a halo, in gilt. Italian artist Giotto (ca. 1266 – 1337), has clothed her in a silken veil and robe with bands of embroidery called tiraz, with Arabic lettering. Such fine veils which covered most of the body were typical for wealthy Muslim women of the courts. The Christ child is also wrapped in a fine fabric with embroidered bands. The painter has created an image of the most central figures in Christianity for a setting where worship took place, using a typical Islamic luxury fabric and style of dress for Muslim women. The embroidery bands in Giotto’s painting are not legible, but such tiraz bands had blessings in Arabic from the Qur’an, alternating with geometric designs. The fabric was used to create an image of great beauty using the most rare and expensive fabrics of the time, which were imported from North Africa or the Levant.

This painting is only one of many examples of Madonna and Child paintings, some of which show halos modeled on fine Islamic metalwork, with Arabic script engraved around the circles. In this example, the halos contain geometric designs in gold, but the archway around the painting shows faint imitations of Arabic lettering. The ports and cities that exported these goods from the East were contested between Christian and Muslim armies, but the fabrics and other luxury items were not controversial even in sacred art, but precious and desirable.

Image source: Giotto, Italian (ca. 1266 – 1337), Madonna and Child, painted ca. 1320/1330, tempera on pane Dimensions: 85.5 x 62 cm (33 11/16 x 24 7/16 in.) framed: 128.3 x 72.1 x 5.1 cm (50 1/2 x 28 3/8 x 2 in.), National Gallery of Art, Washington DC, Samuel H. Kress Collection, Accession No.1939.1.256, https://images.nga.gov/?service=asset&action=show_zoom_window_popup&language=en&asset=20008&location=grid&asset_list=20008&basket_item_id=undefined. (expand image to show detail online)

Glassware

About 1260

Image source: Syria, ca. 1260 (Crusade, glass with gilding and enamel), Walters Art Museum, Accession Number 47.18, http://art.thewalters.org/detail/30828/beaker-2/.

The Crusades and Glassmaking Technology

In their book Islamic Technology, Donald Hill and Ahmed al-Hassan cite the text of a treaty between Bohemond VII, prince of the Syrian city of Antioch, and the Doge (ruler) of the Italian city-state of Venice:

a treaty for the transfer of technology was drawn up in June A.D. 1277. . . . It was through this treaty that the secrets of Syrian glassmaking were brought to Venice, everything necessary being imported directly from Syria—raw materials as well as the expertise of Syrian-Arab craftsmen. Once it had learnt them, Venice guarded the secrets of technology with great care, monopolizing European glass manufacture until the techniques became known in seventeenth century France.

Text Source: Ahmed al-Hassan and Donald Hill, Islamic Technology (New York: Cambridge University Press/UNESCO, 1987), p. 153.

Rosamond Mack, in her book From Bazaar to Piazza, describes the Venetian island of Murano where glass-making was isolated both for its fire hazard, but also to protect its secrets. Mack acknowledges the influence on Venetian glass of Islamic and Byzantine techniques and decorative styles. Before the Crusades, Venetian artisans made glass. During the Crusades, their industry benefitted from trade relations and transfers of material. They imported alkali, an essential ingredient, “through its merchant colonies in the crusader states. A treaty of 1277 between Doge Giacomo Contarini and Bohemond VII, prince of Antioch, mentions duties on broken glass loaded at Tripoli that served as raw material in Venice. Production and markets were varied by the end of the Crusades; “water bottles and scent flasks and other such graceful objects of glass” were proudly borne in the inaugural procession for Doge Lorenzo Tiepolo in 1268, the Polo brothers opened the Oriental market for Venetian glass beyond the Alps.”

Text Source: Rosamond Mack, From Bazaar to Piazza: Islamic Trade and Italian Art, 1300–1600 [Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002], p. 113.)

For more on Islamic glass technology and its history, see “Glass” at http://islamicspain.tv/Arts-and-Science/The-Culture-of-Al-Andalus/index.html.

Islamic Artistic Influences in the Basilica of San Francesco

After St. Francis’s death, the simple man whose life was a symbol of richness of spirit and material poverty very quickly became a canonized saint. On 16 July 1228, Francis was canonized by Pope Gregory IX in Assisi, and he laid the foundation stone of the new church the following day. The pope arranged to build a worthy tomb and basilica, site of pilgrimage, and a convent as home for the Friars Minor, the Order of the Franciscans. It was designed by Maestro Jacopo Tedesco, the most famous architect of his time in Italy, and supervised by Brother Elias, one of St. Francis’s first followers. It was built between 1230 and 1253, with a Lower Church and an Upper Church, and a crypt in which St. Francis is buried. It became a UNESCO world heritage site in 2000.

Basilica of San Francesco

The Meanings of Islamic Influence in the Basilica

Michael Calabria finds that Francis’s humble encounter with al-Kamil had a deep impact on the expression of his faith. Francis returned from Egypt and wrote a letter to the rulers, saying that there should be a sound used to call worshippers to prayer—such bells come from the Franciscan tradition. He was impressed with the participation of all in the five daily Islamic prayers, and with the names of God. He wrote a prayer of supplication to God, unlike any other in the tradition of Christian sacred literature at that time. The last gesture of Francis’s life was that he asked to be laid on the bare ground, perhaps a gesture of submission to God. These are very reminiscent of aspects of Islamic worship he would have witnessed during his time in al-Kamil’s presence.

As for the Basilica, the magnificent structure contradicts Francis’ message of poverty, but it is not so ironic that the Basilica has unconsciously perhaps, drawn elements from the Islamic society he visited into the realm of western Christendom. This arose, says Calabria, “not by trouncing or triumphing, or confronting or coercing, but in a seamless blending of styles arising simply from a mutual appreciation and sharing what is beautiful. In this way the Basilica can be said to be a fitting reflection of what occurred in Francis’ own personal encounter with Islam, inspiring his own faith and prayer.” What was created, he said, is a common visual language across cultural and religious boundaries. This common vision and language of beauty is too often forgotten a world that in more recent centuries has accepted rigid dichotomies of east and west, European and African, European and Asian, Christian and Muslim, to the exclusion of a deeper and more integral unity.”

Text and image sources: Calabria, Michael D. “Seeing Stars: Islamic Decorative Motifs in the Basilica of St. Francis.” Select Proceedings from the First International Conference on Franciscan Studies: The World of St. Francis of Assisi, Siena, Italy, July 16-20, 2015. Pp. 63-72; also, lecture at Georgetown University by Fr. Michael Calabria, “The Confluence of Cultures: Italo-Islamic Art and the Basilica of St. Francis in Assisi” (View video lecture at the Center for Contemporary Arab Studies at Georgetown University, August 2014, at http://vimeo.com/226482289).

Other images of the Basilica of St. Francis of Assisi at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Basilica_di_San_Francesco_(Assisi), Roberto Ferrari from Campogalliano (Modena), Italy under Wikimedia commons; upper & lower churches: Basilica of St. Francis by Berthold Werner (Own work) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

Mathematical and Scientific Exchanges

Mathematics is part of trade for at least three reasons: (1) It is needed in navigation on the seas, along with astronomy. (2) Merchants need to keep records of goods and money, especially when their routes cover many lands, and when they finance their journeys with other people’s money—such as families, trade agreements, or lenders. For that, they need accounting, or bookkeeping. (3) Another important use of mathematics is in building and engineering. When trade grows, people want to build roads, walls to defend their cities, and fine buildings to show off their wealth. Mathematics was also a source of intellectual pride, as rulers and scholars matched wits to solve mathematical problems, out of curiosity or the desire to discover new truths. During the period of the Crusades and after—especially during the 12th century and beyond, mathematical knowledge from Islamic lands entered Europe through translations, along with many other kinds of scientific and technical knowledge. As you may know, one of those innovations was the use of Hindi-Arabic numerals. Read about mathematician Fibonacci who helped introduce those numerals for all of the purposes above.

Fibonacci in North Africa and His Book Liber Abaci

Fibonacci

Image credits: “Roots: Legacy of Fibonacci,” 1228 edition of Liber Abaci and image of Fibonacci at Emma Bell, Chalkdust: a Magazine for the Mathematically Curious, http://chalkdustmagazine.com/features/roots-legacy-of-fibonacci/.

To learn about many other contributions in mathematics, science, technology and the arts, visit http://islamicspain.tv/Arts-and-Science/The-Culture-of-Al-Andalus/index.html.

Culinary and Agricultural Exchanges from the Crusades

Sugar

Like all plants, the sugar cane plant is a grass that manufactures sugar from sunlight and water. The juice in the stalk is very sweet. People liked its taste and started growing it thousands of years ago in Southeast Asia. Over the centuries, people brought the knowledge of how to grow sugarcane to India, then to Persia and across medieval Muslim lands to Spain. Muslim traders and migrating farmers brought sugar to the Mediterranean lands, including the Iberian Peninsula, around 1000. Europeans became aware of the sweet treat through visits to Muslim Spain, and through the luxury trade across the Mediterranean, carried on mainly by Italian merchants. Sugar was a rare luxury accessible only to the rich.

Crusaders who conquered what became the Latin Crusader States found sugar already being cultivated and refined. They learned these techniques from the Arabs and continued its cultivation, with the main center of the industry in Tyre in Lebanon. They also learned to use it in pastries made with fine wheat flour, fruit preservation, and candies, the name coming from the Arabic word qandi. The sugar that Europeans enjoyed during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries came from the Crusader lands in the East.

Spices

Other items that Europeans learned of during the Crusades, and then began to import in greater amounts were spices and herbs. The most important was balm (Melissa officinalis), used in church services. Others were cinnamon, pepper, cloves, cardamom, cumin and various Mediterranean herbs such as oregano and sage, which were used in cooking. A merchant’s guide from Florence of 1310–1340 lists 288 “Spices,” which included “seasonings, perfumes, dyestuffs and medicinal of Oriental and African origin.” Among the long list are chemicals used in coloring cloth and preserving food, such as alum, wax, gallnuts, and indigo, dyes for making blue, red, yellow, and black fish glue, gum Arabic, soda ash, and many other things. Among the spices we think of as seasonings, they imported citron, fennel, pepper, poppies, sumac, cloves, cinnamon, caraway, cardamom, ginger, mace (nutmeg) cumin, myrrh, frankincense, sandalwood, and rose water, to name just a few.

Rice was first grown in tropical Southeast Asia, where it spread to China and beyond in the east, and India and Persia, and Iraq before reaching Mediterranean lands with irrigation systems that would allow it to grow. Rice was not at all common in Europe’s cold climate, but was a rare import. It was listed in the same merchant’s guide, as a “spice” which seems to have meant something rare and tasty.

Source of text: Wright, Clifford A. A Mediterranean Feast: <> Story of the Birth of the Celebrated Cuisines of the Mediterranean, from the Merchants of Venice to the Barbary Crosaird, (Morrow, 1999), http://www.cliffordawright.com/caw/food/entries/display.php/topic_id/23/id/99/. ; Robert S. Lopez and Irving W. Raymond, translators, Medieval Trade in the Mediterranean World: Illustrative Documents (New York: Columbia University Press, 2001), pp. 108-114. Excerpts from book on medieval trade documents (List of 88 “spices”).

Macaroni and Pasta

a medieval handbook of health

The history of pasta is very old, and was made from many types of grain. When the thin dough was dried, it was easy to store, light to pack for travels, and ready to eat after boiling in water a short time. It could be combined with any meat, sauce, or vegetable. It could even be eaten sweet, cooked with milk and honey. There is a popular legend that Marco Polo learned of pasta in China, but it was there before he ever went, even though he surely learned about new types on his 13th century travels to China. Durum wheat—semolina—was introduced to Europe through Muslim Spain, and the Crusaders were also exposed to it from the 11th century in Syria. Durum wheat itself probably originated in Central Asia, in today’s Afghanistan, and spread across Muslim lands, like many other foods.

Source: http://www.katjaorlova.com/PastaClass.html. Image from the The Tacuinum Sanitatis, a medieval handbook of health, a translation and compilation from the Taqwīm as‑Sihhah (Maintenance of Health), an eleventh-century Arab medical treatise by Ibn Butlan of Baghdad. This is from a Vienna edition, showing pasta being rolled, cut and dried on a rack.